William Harvey's

On the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals.

Harvey states the greater functions and roles of the heart as a center

for liveliness, warmth, and nourishment:

In the first place, since death is a corruption which takes place through deficiency of heat, and since all living things are warm, all dying things cold, there must be a particular seat and fountain, a kind of home and hearth, where the cherisher of nature, the original of the native fire, is stored and preserved; from which heat and life are dispensed to all parts as from a fountain head; from which sustenance may be derived; and upon which concoction and nutrition, and all vegetative energy may depend. Now, that the heart is this place, that the heart is the principle of life, and that all passes in the manner just mentioned, I trust no one will deny.

Harvey asserts this to be true based on the facts that all living things are warm, all dead things are cold, tissue which is cut off from blood supply dies, and because the circulatory system is the only practical means the body possesses to nourish the entire body with foods ingested in the locally limited digestive system.

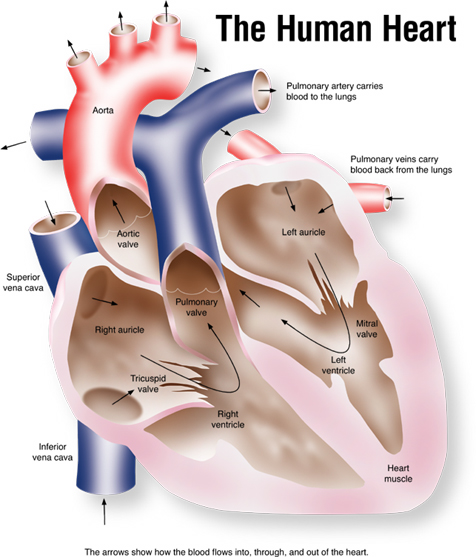

Harvey observes that while insects have no heart and amphibians, reptiles,

and other lower animals have a single ventricle in their hearts, mammals

and birds have the highly efficient four-chambered heart. This, he says,

is why:

In all the larger and warmer animals which have

red blood, there was need of an impeller of the nutritive fluid, and

that, perchance, possessing a considerable amount of power. In fishes,

serpents, lizards, tortoises, frogs, and others of the same kind there

is a heart present, furnished with both an auricle and a ventricle,

whence it is perfectly true, as Aristotle has observed, that no sanguineous

animal is without a heart, by the impelling power of which the nutritive

fluid is forced, both with greater vigour and rapidity, to a greater

distance; and not merely agitated by an auricle, as it is in lower forms.

And then in regard to animals that are yet larger, warmer, and more

perfect, as they abound in blood, which is always hotter and more spirituous,

and which possess bodies of greater size and consistency, these require

a larger, stronger, and more fleshy heart, in order that the nutritive

fluid may be propelled with yet greater force and celerity. And further,

inasmuch as the more perfect animals require a still more perfect nutrition,

and a larger supply of native heat, in order that the aliment may be

thoroughly concocted and acquire the last degree of perfection, they

required both lungs and a second ventricle, which should force the nutritive

fluid through them.